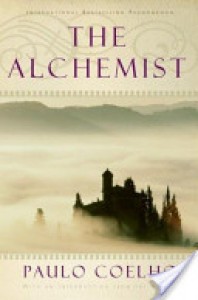

Review: The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho

This book is primarily a detailing of a philosophy via a plot rather than a book focused on the story itself. The author has a carefully constructed worldview that is completely evident throughout the entire story, which is appropriate given that the story of the book is a metaphor for the experience of reading the book itself.

Over the course of the book, the main character goes on a journey of self discovery after having a dream about finding treasure by the great pyramids in Egypt. Rather than being a direct path from points A to B, his journey acts as a means for him to acquire knowledge about the universe, knowledge that is inherent to all of creation and is within all of us from the start were we to listen. For this reason, the main character isn't gaining knowledge over the course of the book so much as he is gaining the ability to recognize what he already knows about the world. The author seems to use the book to suppose that this is true within our world, too. We already have the knowledge within us that the book discusses externally, we merely have to learn to accept it. In the conclusion of the book, it turns out that the treasure that the main character was looking for was in the location where he first had his dream, before he had even begun his journey. By returning to the start to find what he'd been searching for, the author reinforces the idea that all the knowledge gained over the course of his journey was within the main character, as well as the reader, all throughout and this has just been a means of bringing it to the surface and reinforcing it. On the other hand, he never could have found his treasure without the knowledge being brought out in him by the journey, so it doesn't negate the necessity of the act even if he returned to the start.

Altogether the book feels compelling. The philosophy the author expresses is a fascinating one, if not one that I would ever subscribe to. One interesting aspect of the novel is how the vast majority of characters are unnamed. They're perpetually referred to as the Englishman or the Alchemist or something of that variety. The only exception to this rule that I can recall is Fatima, who is also one of only two or three women in the novel. By removing names from the characters, they're more free to act as wider aspects of humanity, furthering the book's universalist vision that we aren't separated by things such as family, but are connected to one another inherently and are only separated by what our purpose in life is. The author finds a way to incorporate his message into every aspect very well, weaving together the narrative so that it all compliments each other.